Date: 7 May 2015

Tim Kempster, the company’s managing director, looks at how fire safety must be policed by responsible people. Not so long ago, fire safety was largely about common sense. Before modern fire and building regulations, responsibility for a building’s safety, and the safety of its occupants, depended largely on how seriously a building owner took that responsibility. Now, responsibility is a legal term because fire regulations in the different UK jurisdictions all require commercial premises to have a named “responsible person” to ensure fire safety.

That person’s task – or “people,” as there can be more than one - involves a number of steps and processes, including carrying out a fire risk assessment, planning for an emergency, staff training and carrying out regular fire drills. It’s about identifying risk and contingency planning.

In England, legislation falls under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005, and there are large penalties for those who fail to discharge their responsibility. Nor does it matter if a fire has actually happened. What matters is whether safety inspectors from the fire services are satisfied that the responsible person (or people) has discharged their responsibilities.

The most important duty of a responsible person is to look holistically at their business and make an assessment of possible risk, identify areas where fire is most likely to start, put in place strategies for dealing with it and, of course, plan for a safe evacuation – including those with mobility problems.

That’s not to say that the responsible person must become an expert in fire safety; merely that he or she appoints an expert who does know what they’re doing, and that recommendations are understood, implemented, regularly reviewed, and practiced.

It all starts with a fire risk assessment, designed to identify problem areas, consider containment and other strategies, and implement passive and active solutions to meet every conceivable risk.

But it goes beyond that because, nowadays, risk assessment should be about the multiplicity of threats faced by a business or building; a multi-disciplinary approach to assessing all hazards, not just fire risk – from power failure to cyber attack, from civil disorder to explosive detonation – and arriving at risk assessments that, hopefully, illuminate how that that building should be protected.

In other words, a risk business-critical assessment should be about more than fire and, at Wrightstyle, we recommend taking the widest-possible view – looking beyond fire safety regulation to also consider all possible risks against that building’s occupants, structure, resources and continuity of operations.

There are a number of assessment methodologies to understand the potential threats, identify the assets to be protected, and how best to mitigate against those risks. That assessment then guides thinking on acceptable risks and the cost-effectiveness of the measures proposed.

Our view is that compliance with fire regulations, while important and necessary, is not enough, because dealing with a fire is much more than ensuring human safety and limiting building damage. At the very least, fire can be disruptive. At most, it can shut down a business, perhaps permanently, or destroy information vital to continued operations.

A robust fire risk assessment should therefore be about more than the practicalities of regulatory compliance. If fire does happen, can we quickly move manufacturing elsewhere? If our computers are damaged, is all that business-critical information also held elsewhere? It’s worth remembering that, sometimes, the worst does happen.

Although a robust risk assessment will address issues such as the storage of flammable materials, most fires start from the most insignificant of causes. For example, a 31-year-old man from Wales was jailed for six years recently for accidentally causing £26 million worth of damage to his place of employment in 2012 – and putting 100 people out of work. His crime? Sneaking off for a cigarette and not properly disposing of it.

But however a fire starts, it is spread through three methods: convection, conduction and radiation, of which convection is the most dangerous. This is when smoke from the fire becomes trapped by the roof, spreading in all directions to form a deepening layer. Smoke, rather than fire, is often the real danger.

Materials such as metal can absorb heat and transmit it to other rooms by conduction, where it can cause new fires to break out. Radiation transfers heat in the air, until it too sets off secondary fires, spreading the danger away from its original location.

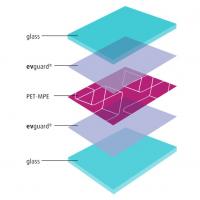

Modern glazing systems can provide complete protection against convection, conduction and radiation – whether as curtain walling, or internal doors or fire screens – for up to two hours, giving more than enough time for a safe evacuation.

However, “responsible people” should also ensure that the fire glass and its framing systems have proven compatibility. That means insisting on comprehensive fire test certification that covers both elements because, in a fire, the glass and its frame have to function together to prevent the spread of fire, smoke or toxic gases. If one fails, both fail, with potentially catastrophic consequences.

At Wrightstyle, we’ve invested in compatible fire certification in the UK, USA and Far East – a reflection of our global business, and our confidence in our systems’ performance. There again, we like to think of ourselves as responsible people.

Ends

For further information: Jane Embury, Wrightstyle +44 (0) 1380 722 239 jane.embury@wrightstyle.co.uk

Media enquiries to Charlie Laidlaw, David Gray PR Charlie.laidlaw@yahoo.co.uk +44 (0) 1620 844736 or (m) +44 (0) 7890 396518

Add new comment