Date: 18 October 2013

Wrightstyle has supplied to a number of airports including London Luton, Gatwick and Heathrow and, internationally, Doha, Dubai and Taiwan.

Kenya has been much in the news recently, and not for the right reasons. The Westgate shopping mall massacre in which at least 67 people died is a shocking reminder that any building where large numbers of people gather can be a terrorist target.

That threat is most real at airports, which can have a pivotal role in regional or national economies and, for the terrorists, significant news value. Airports have therefore seen the greatest investment in security and building research, although the recent Westgate attack is a reminder that the threat is much wider.

Nor is the threat confined to larger hub airports. The 2007 attack at Glasgow airport underlines how terrorism can be both national or local, meticulously planned for maximum effect or simply opportunistic.

But it would be simplistic to consider airport security purely in terms of terrorist threat. In August, Kenya was again in the world’s media spotlight following a major fire at Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta airport, the busiest in East Africa, and of major economic importance for the country – both for inward tourism and exports, mainly cut flowers.

The catastrophic fire, most probably started by faulty wiring, demonstrates how a major infrastructure asset can quickly become a national liability. The airport, built in an age before modern fire regulations and protective systems, was extensively damaged, closing off a vital transport gateway. However, perhaps remarkably, there were no casualties.

The Nairobi fire is a stark reminder of the importance of identifying every conceivable threat, that strategies to deal with them are robustly examined, and emergency procedures routinely tested – which wasn’t the case in Nairobi with its aged infrastructure, inadequate emergency equipment and poor response planning.

Countering those threats starts with a comprehensive assessment of the likely (or unlikely) risks the airport might face in terms of an accidental or deliberate interruption to its operations. Modern building safety is largely determined by taking a multi-disciplinary approach to assessing those hazards – from power failure to cyber attack, from civil disorder to fire and explosive detonation.

For an airport, other factors might have to be considered – from the kinds of threat specific to that country or region, to the airlines that make use of the facility. The fact is that, while terrorism is often a blunt instrument involving random carnage, it can also be targeted more specifically.

There are a number of assessment methodologies to understand the potential threats, identify the assets to be protected, and how best to mitigate against those risks. That assessment then guides the design team in determining acceptable risks and the cost-effectiveness of the measures proposed, both airside and landside.

The UK has been at the forefront of airport safety, largely because of the historical threats posed by Irish terrorists, which included mortar bombs being fired onto the runway at London Heathrow in 1994. They failed to detonate but underlined how airport security is an issue that has to be considered outside, not just inside, the airport’s perimeter.

That, in essence, is the airport designer’s conundrum: how to build a facility able to safely handle large numbers of people, while making their experience as hassle-free as possible. Since 1996, the UK’s Department for Transport has published guidance in the form of Aviation Security in Airport Development (ASIAD).

The guidance covers many of an airport’s critical functions, from security checks on passengers to aircraft hold baggage, from the location of car parks to the glazed elements in the building’s design. The guidance also now includes the design of areas immediately outside terminal buildings to create an exclusion zone for unauthorized vehicles.

Stand-off distance is an important consideration. A bomb detonating at seven metres from the terminal façade will, depending on the size of the bomb and type of explosive, generate blast pressure of up to one ton per square foot. At 30 metres, blast pressure falls to one-tenth of a ton per square foot – within building regulation parameters on structural integrity.

Modern building design, in airports as elsewhere, now makes extensive use of glass. It brings in ambient light and creates a more pleasant interior environment. (Interestingly, a Which survey earlier this year found that London Luton airport has the lowest passenger satisfaction of any UK airport – a facility that many considered gloomy, and which is one of the oldest terminals in the UK).

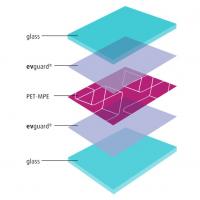

The extensive use of glass has come about as a result of investment in innovation, both to develop new laminated glass types and framing systems able to withstand blast pressure, as well as to accurately evaluate those systems using a variety of assessment and computational tools.

At Wrightstyle, we have gone beyond computational assessment to also conduct live bomb testing. One test involved a simulated lorry bomb attack (500 kg of TNT-equivalent explosive) detonated 75 metres from the test rig, followed by a simulated car bomb attack on the same glazing system (100 kg of explosive), detonated at a distance of 20 metres. Both tests were equally successful.

Our compatible systems, with the glass and steel framing systems tested together, are accredited to EU, US and Asia Pacific standards. Our strong advice is to always specify the glass and framing as one unit: in a real fire or terrorist situation, the glass will only be as protective as its frame, and vice versa.

As recent events in Kenya have shown, both fire and terrorist attack are potent threats to be assessed, comprehensively guarded against, and with regular rehearsals to ensure that response teams can deal adequately with any emergency.

That multi-dimensional approach also extends across the built environment, developing next-generation products and systems to ensure new levels of fire and terrorist protection. The specialist glass and glazing industry remains at the forefront of that innovative research process.

For an overview of Wrightstyle systems for the airports sector, click www.wrightstyle.co.uk

Ends

For further information: Jane Embury, Wrightstyle +44 (0) 1380 722 239 jane.embury@wrightstyle.co.uk

Media enquiries to Charlie Laidlaw, David Gray PR Charlie.laidlaw@yahoo.co.uk +44 (0) 1620 844736 (m) +44 (0) 7890 396518

Add new comment