Date: 4 May 2016

Despite the housing boom of post-war Britain, the advent of modern building techniques and the introduction of cutting-edge architectural design, homes constructed during this period were largely draughty and difficult to keep warm. Fire remained a central source of warmth as central heating was a rarity in even the most prosperous households.

As the austerity experienced during wartime continued to subside, the provision of new housing grew. Between 1960 and 1970 close to half a million homes were constructed across the country. High-rise tower blocks made up the bulk of production and provided critical housing stock for urban populations, yet in many cases, the homes were poorly insulated.

During the first half of this decade, the majority of homes were fitted with single glazing. While the glass provided shelter from the elements, it often caused problems with internal condensation causing mould growth, which had the potential to cause health issues for homeowners.

Similarly, lack of effective water resistance meant that residents were often cold and vulnerable to rain leakages. The faults undermined public confidence in the construction industry and spurred policy makers to examine the quality and energy performance of its output.

In an attempt to ensure future properties provided secure and comfortable homes, the government introduced the first national Building Regulations in 1965. The regulations laid out a number of critical provisions including the first limits on the amount of energy that could be lost through the fabric of new houses, incentivising builders to invest in technologies and materials that cut energy wastage.

The Introduction of Double Glazing

Although double glazing is thought to have originated in Scotland during the Victorian era, and was common in US homes during the 1940s and 1950s, it only really gained popularity in the UK in the 1970s. Until this point, relaxed building codes and the cost of materials meant that few homes were fitted with double-glazed units.

The turning point came during the 1973 oil crisis, during which the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries declared an embargo on oil, triggering the UK to rethink its dependence on foreign resources and consider how sustainable products, such as double glazing, could be used to help keep homes warm.

Coupled with this, as the country entered the 1980s, household affluence reached new heights and people became more concerned about building robust homes, fitted with the latest in modern household technology. As a result, double glazing really took off.

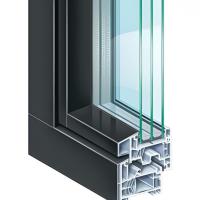

Windows had, until that time, been manufactured using steel or timber frames but the late 80s, saw the rise of uPVC windows and doors, manufactured from a thermoplastic polymer known as un-plasticised polyvinyl chloride, a rigid and cost-effective plastic ideal for building materials.

The new windows were air-tight and incorporated double glazing units (DGUs) to provide increased levels of thermal efficiency.

Between 1979 and 1999, the percentage of homes fitted with DGUs rose from 16 per cent to 68 per cent as more people began to appreciate their thermally insulating properties, and the considerably reduced levels of internal condensation, which helped create a healthier environment.

21st Century Sustainability

While the pre-millennial governments were focussed on creating housing stock for the post-war population, the policy-makers of the 21st century saw house building as a fundamental tool in helping them achieve their new zero carbon emission targets.

In 2002, low-emissivity glass became a mandatory requirement for new homes, forcing house builders to ensure that CO2 emissions from new buildings were drastically reduced.

This was followed by the introduction of ‘Code for Sustainable Homes’ in 2006, which aimed to ensure the sustainability of new-build homes. At this time, the government also supported the development of the Zero Carbon Hub, a non-profit organisation responsible for achieving the government’s zero carbon homes initiative in England from 2016.

In line with the tightening of regulations and a focus on eco-friendly practices, a range of high performing glazing solutions began to emerge. Ultra-clear low-iron glass increased in popularity, as it helped to maximise passive energy gains from the sun, enabling occupiers to save on heating costs during the winter.

In addition, low-iron glass became popular for use in solar photovoltaics as it allowed for high solar energy transmittance, strength and durability.

Looking Ahead

Despite the government recently announcing the dropping of its zero carbon buildings policy, meaning no change in building regulations in 2016, energy-efficient homes are still very much on the agenda today. Revised EU legislation over the past decade has set stringent energy targets for all Member States, urging them to ensure all new buildings are nearly zero-carbon by end of 2020.

In support of these objectives, the glazing industry is continuing to produce innovative solutions that help increase thermal efficiency and combat carbon emissions. Leading the developments are ‘smart’ double glazing solutions, which can deliver U-Values as low as 0.9W/m2K, a figure previously only associated with triple-glazed solutions. This is achieved by combining two panes of low-emissivity glass in one unit, to give the same performance as triple glazing. In adding the extra coating on the room side, heat is reflected back into the house, reducing the amount of radiant heat loss through the glass and retaining warmth within the building.

As the industry evolves to meet energy-efficiency standards, Pilkington United Kingdom Limited will continue to be at the forefront of product development, combing expertise with innovation to create glazing solutions that address the growing appetite for sustainable homes.

600450

600450

Add new comment