Date: 19 February 2009

It’s defined as a rapid, persistent chemical change that releases heat and light and is accompanied by flame, especially the exothermic oxidation of a combustible substance.

Definitions aside, fire is also dangerous, although it can be tamed or contained. When it isn’t, as it wasn’t five years ago at a complex of six garment factories in Dhaka, Bangladesh it can be lethal.

In that fire, men and women, most in their teens and early twenties, tried to escape down a narrow stairway barely five feet wide. In the ensuing stampede, seven women were trampled to death and fifty injured.

However, what made this fire worse was that it wasn’t an isolated incident. In November 2000, another 45 Bangladeshi garment workers were killed and 100 injured in a factory fire caused by an electrical short circuit. Among the victims were ten children. The stairwell was so crowded that workers broke windows and threw themselves out.

In 2001, 24 workers, mostly women, died in yet another factory fire in Dhaka, bringing the total number of lives lost in factory fires in the country to 84 in that one year alone. The fire, caused by faulty electrics, did not spread far – but the tragedy was again exacerbated by workers from five different production units converging on the same escape stairway.

Locally, a leading expert on fire safety, Dr. Nizamuddin Ahmed, professor of architecture at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, said that the tragedies happened because proper architectural practices were not followed – in particular, compartmentation.

Bangladesh has in recent years made real progress in establishing and enforcing fire and safety regulations but, as a developing nation, many of its factories are still operating in conditions that would be unacceptable in the west.

That’s not to criticise Bangladesh but to highlight how far fire and safety regulations have transformed the architectural landscape of the developed world to create offices and factories that are fundamentally safe. Unlike poorer nations, we can better afford to incorporate fire safety into the fabric of the building.

The sobering fact is that, each year, fire kills an estimated 166,000 people worldwide – that’s nearly 19 fatalities every hour of every day. Some estimates suggest nearly 300,000 deaths per year. The International Technical Committee for the Prevention and Extinction of Fire (CTIF) estimates that the annual cost of fire damage adds up to a whopping 1% of international GDP or €400 billion.

The fire regulations on which building safety depend are themselves based on an understanding of fire dynamics - the fundamental relationship between fuel, oxygen and heat – the so-called fire triangle on which all fires, intentional or otherwise, depend.

Get those three elements together and the fire triangle is joined by a fourth element - the chemical chain reaction that is actually the fire. In technical jargon, the triangle of combustion then becomes a tetrahedron.

It’s a geometry that can either be friend or foe, as fuel and oxygen molecules gain energy and become active. This molecular energy is then transferred to other fuel and oxygen molecules to create and sustain the chain reaction.

In an uncontrolled fire in a building, how it spreads depends on a whole range of factors - from the type of fuel (everything from ceiling tiles to furniture) to building construction and ventilation.

Taming fire generally involves the removal of heat, in most cases using water to soak up heat generated by the fire. This turns the water into steam, thereby robbing the fire of the heat used. That’s what a building’s sprinkler system is there to do.

Without energy in the form of heat, the fire cannot heat unburned fuel to ignition temperature and the fire will eventually go out. In addition, water acts to smother the flames and suffocate the fire.

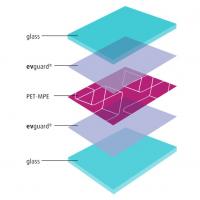

But sprinkler systems can only suppress. What is also needed is containment – to prevent the fire spreading from its original location. Those protective barriers, often external curtain walling or internal glass screens, must also provide escape routes for the building’s occupants – what was lacking in those fires in Bangladesh.

That’s where fire resistant glass and glazing systems are so important, because modern steel systems are so technically advanced that they have overcome the limitations inherent in the glass itself.

The biggest limitation is that glass softens over a range of 500˚c to 1500˚c. To put that in perspective, a candle flame burns at between 800˚c and 1200˚c. In a typical flashover fire inside a building, temperatures can reach between 1000˚c and 1400˚c.

These temperatures can disrupt the integrity of conventional panes of glass, which can crack and break because of thermal shock and temperature differentials across the exposed face. This will compromise the compartmentation of the building’s interior allowing fire to spread from room to room.

As a fire escalates, the amount of heat produced can grow quickly, spreading like a predator from one fuel source to another – devouring materials that, in turn, will produce gases that are both highly toxic and flammable.

To make things worse, due to thermal expansion, these flammable gases are usually under pressure and able to pass through relatively small holes and gaps in ducts and walls, spreading the fire to other parts of the building. Heat will also be transmitted through internal walls by conduction.

As the fire worsens, and when unburned flammable gases reach auto ignition temperature, or are provided with an additional source of oxygen – for example, from a fractured window - an explosive effect called ‘flashover’ takes place.

Flashover is the most feared phenomenon of any fire fighter and signals several major changes in the fire and the response to it. First, it brings to an end all attempts at search and rescue in the area of the flashover. Simply, there won’t be anybody alive to rescue.

Second, it signals that the fire has reached the end of its growth stage and that it is now fully developed as an inferno. That then signals a change in fire-fighting response because it marks the start of a worse danger – the risk of structural collapse.

However, most fires, including the Bangladeshi examples, all start with only a minimum of real danger – a dropped cigarette, a spark from a faulty wire – and, if dealt with quickly or adequately contained, pose no real threat. That’s where our advanced systems come in.

Wrightstyle’s internal and external steel and glass systems have been tested together to furnace temperatures of well over 1000˚c, testing the strength of the glass, the protective level of the glazing system, and its overall capability to maintain compartmentation in a fire situation.

We’ve also added US testing to our armoury because, in America, immediately after fire exposure, their testing regime also requires the glazing system to then be subjected to a high-pressure fire-hose test, aimed directly onto the super-heated steel and glass assembly and generating a water stream in the region of 30 psi.

In the hose stream test, the longer the fire resistance being applied for, then the longer and more severe is the high-pressure water exposure. This tests the glass for the thermal shock of being deluged and suddenly cooled by the fire fighting services, as well as the building’s own sprinkler system.

Thankfully, in the developed world, large and lethal fires are rare. However, that’s not to say that they don’t happen – merely that the safety features built into the building have worked effectively to reduce the fire’s impact on its fabric and human occupants.

Not so everywhere. In 1993, near Bangkok, Thailand a fire in a toy factory killed 188 people and injured 500 others. The fire quickly spread through several interlinked buildings that had no fire-rated internal compartments – the main reason for the large loss of life.

It’s still ranked as the world’s worst-ever factory fire. The tragedy, as with each of the Bangladeshi factory fires, is that they could have been contained and a great many lives saved.

Ends

For further technical information, please contact Lee Coates

+44 (0) 1380 722 239

lee.coates@wrightstyle.co.uk

For further media information, please contact

Charlie Laidlaw, David Gray PR

+44 (0) 1620 844736 or (mobile) +44 (0) 7890 396518

charlie@davidgraypr.com

For more information on Wrightstyle you can visit the company at www.wrightstyle.co.uk

Add new comment